In the rock-climbing world, there are countless different features you can see when looking up at a rock face for the first time. Some climbers may look for the most blank face they can find, hoping to challenge themselves on dime edges and thin crimps.

Others may search the rock for cracks, fissures and pockets, holding a preference for bomber hand jams and finger locks. But there is one feature above all that seems to attract the eye of a climber; the most obvious feature in climbing’s glossary of terms: the dihedral.

What Are Dihedrals?

In climbing parlance, a dihedral is more commonly known as a corner. When you think of a corner, you probably imagine the space you were sent to in grade school for time out. Or is that just me?

In any case, a corner is defined by two walls or planes meeting at a 90-degree angle. It is the same in rock climbing – a corner, or dihedral, is formed where two rock faces meet at an angle, though it is not often a perfect 90-degree meeting.

How To Master Dihedral Climbing

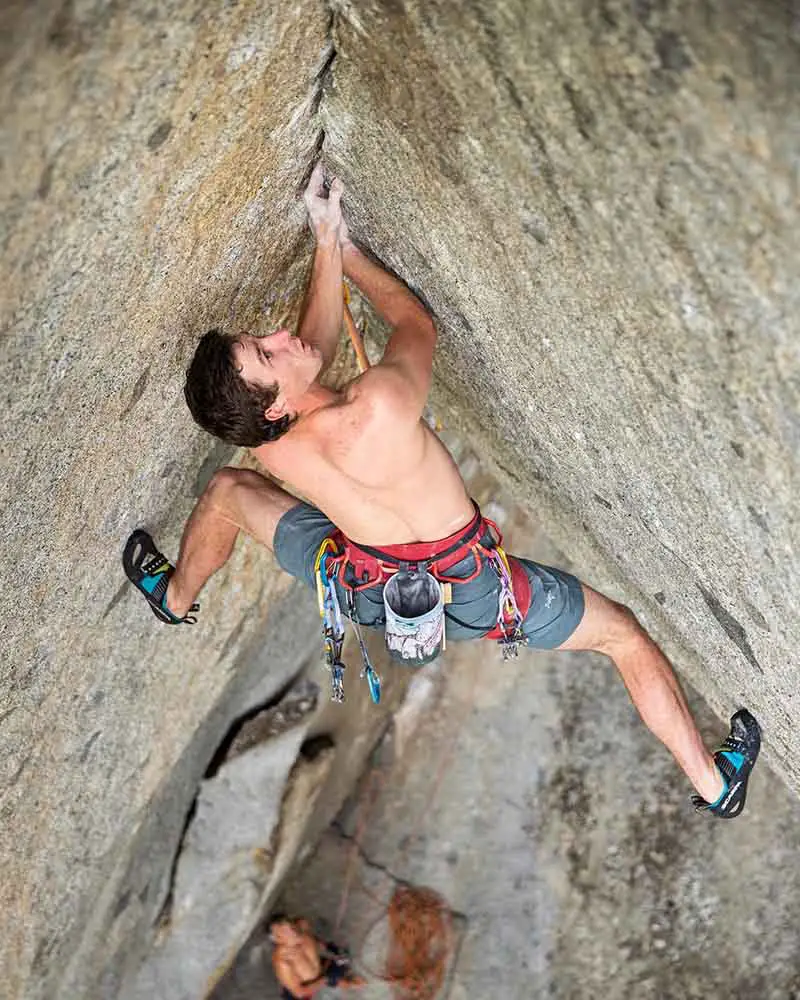

The most classic type of corner is that which features a crack. Where the two planes forming the dihedral meet, there is a slight separation in the rock where a climber may stick a hand or a few fingers. Sometimes, the gap is only large enough for the tips of the fingers to be squeezed in.

A dihedral angle, where two rock planes meet, can just as easily feature a smooth groove. Neither hands, fingers or protection are of much use in situations like this. Luckily, there is more than one way to skin a cat.

Counterforce

When you were a kid, did you ever try to climb your doorframe by pressing both feet and hands against either side, shimmying your way up? Well, I did. Usually, this image brings to mind the technique used for climbing wide chimneys – using opposing forces and tension to keep your body in a wide, parallel crack. However, this principle also applies to climbing corners.

Stemming

Stemming is a technique in climbing whereby the climber uses their hands and feet to press against either side of a corner. By way of this method, they can slowly inch their hands and feet up higher, using opposing forces to maintain tension. This will inherently feel less secure than in a parallel-sided chimney crack. Still, it is an effective tool.

In a dihedral, stemming is often the only way up. Imagine, for example, a 90-degree corner that is near vertical. Even if there is a crack, squeezing yourself – shoulders and all – into the corner is going to get tiring. Before you know it, you’re pumped out. The next moment, you’re falling. As odd as it sounds, coming out of the crack with your feet and smearing against either side of the corner can help take some of the strain off your arms.

Butt & Feet

There is great counterforce generated by pressing your feet against one side of a chimney and your butt/back against the other. It is less common to see a tactic like this used in a dihedral, but by no means is it unheard of. Naturally, it will feel less secure inside of an “open book” feature, but you gotta do what you gotta do.

Shoulder Scumming

In the same vein as the “butt and feet” technique, you can use your shoulder instead of your butt/back. By resting your shoulder against one side of the corner and pressing with one, maybe even two feet, against the other, that counterforce stuff is generated. Until you’ve put in the time on routes that require some shoulder scumming, it is going to hurt, so maybe save it until you are out of other options.

Laybacking

Laybacking is typically only possible in a corner or an arete. Remember the counterforce pressure needed to climb a wide chimney? Well, this angle is about 90- degrees short of parallel. So what do you do? Laybacking requires you to plant your feet more or less flat against one side of the corner and push. Then, gripping the edge of the crack and pulling with your arms, enough counterforce tension is generated to keep you in place. Walking hand over hand and foot over foot, you’re practically walking up the corner!

Gaston

No, not the “Beauty and the Beast,” suave French aristocrat, Gaston. This move was credited to and named after French climber, Gaston Rebuffat. It is the opposite of a side pull where you are pulling from one side in towards your body. Gastoning involves turning your hand to a “thumbs-down” position and pulling away from your body. For me, it helps to imagine someone trying to manually pry open a pair of elevator doors.

Here’s a hypothetical scenario: You are climbing a corner with nothing at the back but a shallow groove instead of a crack. Imagine that the corner forms an obtuse angle (larger or wider than 90 degrees). Obviously, crack climbing technique will not serve you here. Stemming with your feet, and occasionally your hands, will undoubtedly help, but it may not be enough to win the battle.

Maybe, just maybe there is a depression where the two dihedral planes meet; and maybe, just maybe, you can try to pull them apart like the doors of an elevator. Using both hands in this fashion, a climber is able to use the tension to keep themselves in close to the inside of the corner.

Dihedral Climbing Is Fun!

Take it from me, dihedrals make up some of the most fun and exciting climbing! There are so many different ways to climb a corner that you’re spoilt for choice; stemming, laybacking and gastoning are just a few ways of attack. Play around with each of these the next time you’re out on a corner system. Odds are you will end up combining two or more of these techniques, and – if you’re lucky – none of them will singularly be able to carry you all the way to the top! Yay!

Marvel yourself at the wonders of dihedral climbing with the following video!

This is awesome, I never knew Gaston was named after an actual Gaston!

I know right! We use it all the time in climbing, yet most of us don’t even know the history behind it. Pretty cool.