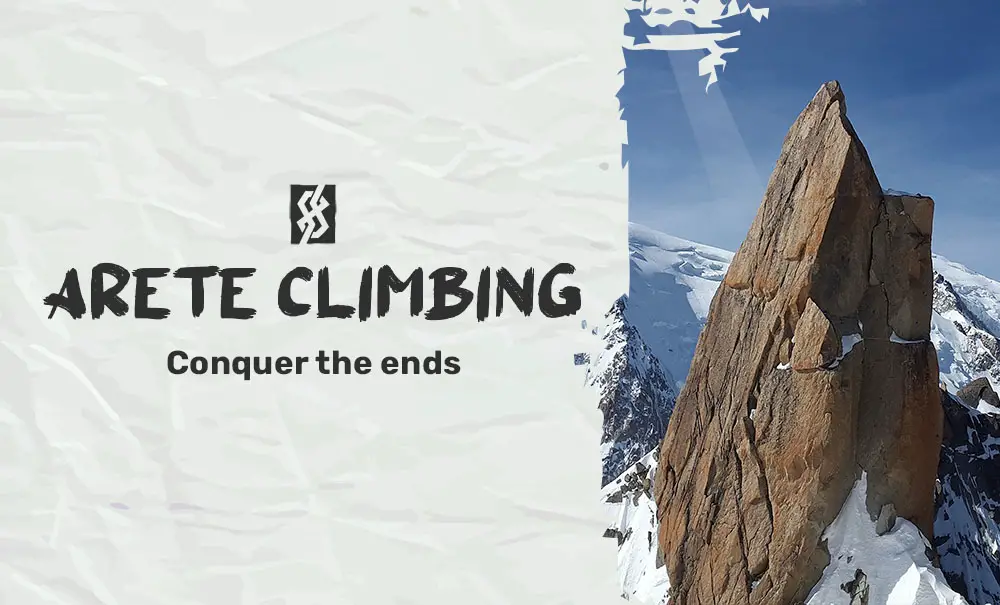

Derived from the French word “arrêt,” meaning “stop,” an arête is anything but a halt in your climbing journey. It’s a thrilling feature that demands finesse, focus, and a flair for the dramatic.

While these features are enticing, you need some skill and expertise to get to the top of an arete. Let’s take a look at how to conquer them like a true climbing artiste!

What Is An Arete?

Arete climbing is a technique where you climb up the sharp edge of a rock face. An arete forms where two flat expanses of rock come together, forming a crisp, defining edge. Imagine two sheets of stone, side by side, merging at a sharp angle. That’s your arête. Think of an arete as the complete opposite of a dihedral.

Arete vs Ridge vs Dihedral: What’s The Difference?

When it comes to climbing, the terms ridge, arête and dihedral might seem like sides of the same mountain, but they’re as different as a leisurely hike and a vertical ascent. Let’s break down these rocky terms and uncover what sets them apart.

Arete

We already know what an arete is, but to remind you, and arete is where two rock faces meet at a more acute angle, forming a narrow, often jagged edge. It’s like the ridge’s edgy cousin and a dihedrals extroverted twin. Arete climbing is more specific and demanding, offering a climb that’s often more technical and exhilarating.

Ridge

A ridge is like the backbone of a mountain, often stretching for miles, connecting peaks, and offering a more expansive, sometimes gentler path for climbers. Picture a long, winding trail along the top of a mountain range, where the slopes fall away on either side. That’s a ridge, a broad feature that can be both a scenic route and a challenging climb, depending on its character.

Dihedral

A dihedral is where two rock planes meet to form an interior angle, creating a corner that often provides more stability and options for hand and foot placements. Unlike an arete, dihedrals often have cracks running along the corner, making it possible for climbers to hand and foot jam their way up. Think of a dihedral as an inverted arete and an arete as an inside-out dihedral.

Is An Arete Dangerous To Climb?

The allure of an arête is undeniable. Many climbers seek the thrill of climbing sketchy aretes, like Nalle Hukkataival. But, climbing aretes is not any more dangerous than doing any other type of climb.

The only time it could become dangerous is when the rope gets in the way. As you ascend an arete, it’s easy for the rope to tangle around your foot. If you fall this can cause you to flip upside down.

It’s also easy to go off-piste when climbing an arete. Most likely, the bolts will be on either side of the arete. If you are clipping on one side but are climbing on the other side of the arete, you might swing out if you fall.

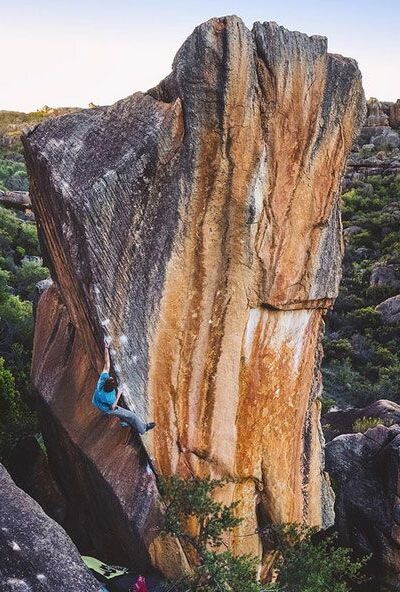

Arete Bouldering

Arete bouldering is exactly what is sounds like. Climbing an arete but boulder style. Bouldering involves climbing shorter routes without rope and crash pads as protection. Climbing an arete boulder require a lot of body tension, intricate movements and pure balance.

Remember Nalle? He is a master arete highballer. Nalle has established some sick arete climbs around the world with his two most famous climbs being Livin Large and The Finnish Line.

Watch Nalle’s inspiring ascent of The Finnish Line:

How To Climb An Arête?

Climbing an arête demands very creative body movement and is often more psychologically challenging than it is physically strenuous. While, just like with ridgelines, the path seems obvious, it is not always as simple as gripping the edge of the arête and hauling yourself up. Depending on the feature, you may need to switch from one side of the edge to the other, heel hook, toe hook, layback and any number of other tricks in order to climb it.

Laybacking

Laybacking is one of the more versatile climbing techniques out there, and it can be a great ally on an arête. Gripping the arête or the lip, a climber places their feet out in front of them and pushes, creating opposition with their hands which are pulling. In this way, shuffling one hand and one foot above the other, a climber can work their way up. This technique requires a lot of endurance as it is the counterforce between the hands and feet that keep the climber from falling.

Laying Back At An Angle

Unlike climbing in a corner, an arête does not often provide a uni-directional experience. When laybacking in a corner, there is usually a flat rock face to press the feet against. In an ideal world, this face will sit at right angles to the lip of the crack that the climber is pulling on. 90 degrees is the happy place for the laybacker.

When laybacking on an arête, the counterforce generated by your feet and hands will only get you so far; there is no flat rock face at right angles to what you are pulling on. Instead, the direction of push with your feet is going to be frighteningly parallel to the direction of pull with your hands. For this reason, it helps to expand your definition of “foothold” to include vertical edges, as well as horizontal. Vertical lips or edges can give the feet much more leverage when laybacking.

Smearing

There will be times in your laybacking career when the rock where you place your feet is flat; featureless. Still, hope is not lost! If there is any texture to the rock at all, odds are you will be able to smear. Smearing is a technique employed when there are no obvious footholds. Using the ball of the foot, the climber relies on grains of rock digging into the sticky rubber of their climbing shoes. If it feels tenuous, that’s because it is! Be prepared – you just might have to smear your feet while your hands grip the arête.

Heel Hook & Toe Hook

While it may feel intuitive to climb an arête with only your hands on the edge and your feet on the rock face, it is not always so. Sometimes, it is helpful to hook your heel or your toe around the arête and pull. This is especially useful on an overhung arête. There are even times when edging with your feet, in a traditional sense, is impossible due to the angle of the rock. In cases like these, the heel and toe hook method is going to be necessary.

Walking The Razor’s Edge

While it might be a once-in-a-blue-moon scenario, arêtes are occasionally climbed by staying on the edge, itself. If the arête is featured, then this might be the most efficient way. This approach does come with a certain amount of exposure, however, and should not be taken lightly. Finding yourself high up on a route, standing on a thin arête with either of the walls angling away from you is a vulnerable place to be. *shivers*

Watch The Rope

When you are climbing an arete, watch the position of the rope (unless you are arete bouldering). We briefly touched upon this earlier, but knowing where the rope is at all times will reduce the chance of a nasty fall.

Depending on which technique you are using to climb the arete, the rope might be in between your legs or on either side. Make sure it doesn’t at any point tangle around your leg.

Barn Dooring

Arete climbing is barndoor central. It’s a horrible feeling when you know your body is about to barndoor out and there is nothing you can do about it. Barn dooring happens when you have too much weight on one side of your body. With arete climbing, you are constantly shifting position so it’s easy to go off balance and barndoor out.

When climbing aretes, try to keep to weight centered, and if you need to move out to a move or need to clip, make sure your feet are stable before making a move.

Arete Climbing Is Fun!

Arête climbing is one of the more enjoyable forms of climbing out there, but it is also one of the most thoughtful and engaging.

Check out this amazing ascent of The Cosmique Arete. Watch how the climber uses a range of techniques, from smearing to heel hooks, toe hooks and laybacking. His arms are kept relatively straight and puts a lot of force through his feet. His every move is elegant, thought out and precise. Truly an inspiring climb from Victor Varoshkin.