Famous Yosemite Climbers

The narrative of rock climbing in the U.S. begins and ends with Yosemite National Park. If you need proof, just look at the grading system we use. If you weren’t aware, it’s called the Yosemite Decimal System.

Everything about the sport in this country is rooted in the historic deeds of world-class climbers who, over the years, have traced lines all over Yosemite’s beautiful walls. This granite valley has always and will continue to attract the best climbers in the world. Their names, as well as their first ascents, makeup volumes of literature and – in the end – there are way too many to cover.

Luckily, as a climbing nerd, I never tire of Yosemite lore! Many of these famous Yosemite climbers and their routes, albeit sandbagged, continue to inspire me, as they do for anyone who has ever been fortunate enough to put their hands on Yosemite stone. So, rope up, and let’s talk rock!

The Golden Age

John Salathé

John Salathé was a Swiss immigrant to the U.S. Along with Anton “Ax” Nelson, John Salathé made the first ascent of the Southwest face of Half Dome in 1946. In 1947, the pair would complete the first ascent of Lost Arrow Spire from the valley floor using the Arrow Chimney – a thousand-foot crack which these days goes free at 5.10 (Yosemite 10, that is). Back then, they used carbon steel pitons, which Salathé – a blacksmith by trade – forged himself. Salathé’s party was the first to use bolted hangers for upward progress. Moreover, it was the first big wall route done in Yosemite Valley and the hardest climb in North America, at the time!

In 1950, with his partner Allen Steck, he climbed the formidable Sentinel Rock. The route is called Steck-Salathé and is still considered to be a test piece for Yosemite chimney/off-width climbing. It is also included in Steve Roper’s Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. Salathé’s accomplishments are impressive on their own, but in the greater context of Yosemite climbing, he helped to pave the way for future generations of adventure seekers.

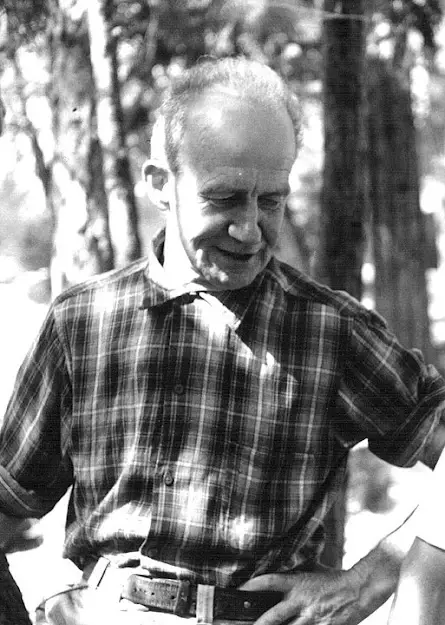

Royal Robbins

Unquestionably, Royal Robbins is the grandfather of rock climbing in Yosemite. You know the rating system that we use to gauge the difficulty of a route? He invented it.

Royal Robbins came to Yosemite Valley in the mid-1950s. Having cut his teeth on the difficult granite of Tahquitz Rock above Idyllwild, CA Robbins wasted no time. He got right to work, putting up daring first ascents all over Yosemite Valley.

In 1957, alongside Mike Sherrick and Jerry Gallwas, Robbins completed the first ascent of the Northwest face of Half Dome – a 2,000 ft wall. In 1960, he and his team completed the second ascent, but the first continuous ascent, of The Nose on El Capitan in 7 days. To engage an old adage, “the list goes on.”

Robbins was one of the first to introduce the art of “Chock Craft” to Yosemite. As opposed to metal pitons, chocks – or “Nuts” – do not require a hammer to be placed; they can be slotted easily into cracks in the rock. More importantly, they can be removed just as easily. This gets at the essence of the philosophy that Robbins and Co. would tout around the valley: Use climbing tactics that have little to no impact on the rock.

These ethics would earn Robbins and his followers the title, “The Valley Christians,” a tongue-in-cheek moniker that was both endearing and disparaging, at the same time. In Basic Rockcraft, a climbing manual that Robbins published in 1971, he elevates, “the silent communion between man and rock.” The remnants of this ethical code, manifest in the Leave-No-Tracers of the outdoor world, are still a powerful voice in the climbing community today. But so are their counterparts.

Warren Harding

No conversation about Yosemite’s Golden Age would be complete without Warren Harding, or “Batso,” as he lovingly became known throughout the climbing community. Warren Harding was about as far from Royal Robbins as you could get. This was a man who drank, smoked and reveled his way up many of his first ascents in Yosemite, drilling bolts, fixing lines and taking long breaks on the ground in between stints on the wall. The “Valley Christians,” people who believed in doing things with a certain amount of style and grace, butted heads with Harding on more than one occasion.

Even so, none of this stopped Harding from making the first ascent of The Nose on El Capitan, the first ascent of The Dawn Wall (which Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson would free climb more than sixty years later), and countless others. If Royal Robbins is the grandfather of Yosemite climbing, then Warren Harding is the wine-drunk great-uncle.

The Stonemasters

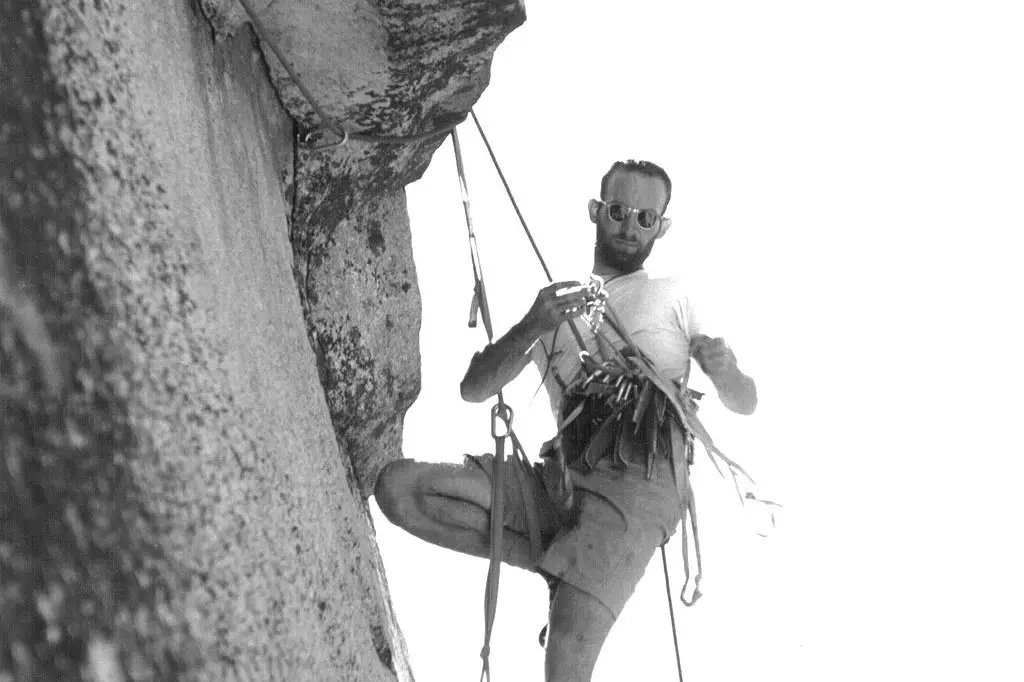

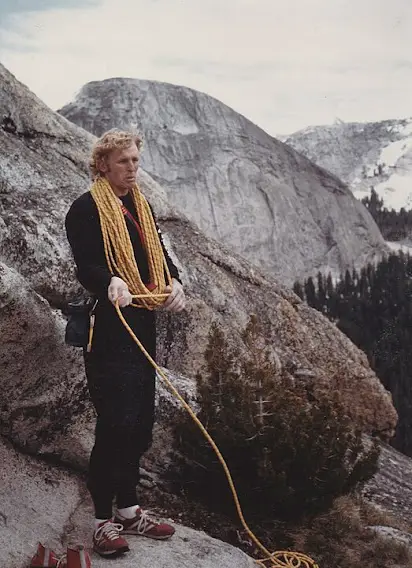

Jim Bridwell

The free climbing revolution in Yosemite begins with Jim Bridwell, a.k.a., “The Bird.” Having apprenticed under the heavy hitters of Yosemite’s Golden Age, Bridwell came along in the seventies to lead a merry band of climbers called The Stonemasters into a new era. Whereas aid climbing tactics had mainly been used to climb Yosemite’s walls, Bridwell popularized the reliance on one’s own hands and feet to carry him up, scaling routes that, for years, everyone had thought to be impossible in a free climbing sense. Moreover, he took the aid game to the next level.

In 1970, Bridwell, alongside John Long and Billy Westbay, did the first one-day ascent of The Nose on El Capitan, something which had taken Harding’s team over 18 months to complete and Robbins’ 7 days in a push. Over the years, The Bird would fly up countless other routes, both free and aid, that to this day are considered the cream of the crop in Yosemite classic climbs – New Dimensions (11a) at Arch Rock, Central Pillar of Frenzy on Middle Cathedral (5.9), Sea of Dreams on El Capitan (VI 5.9 A5). I’ve been on a few of his routes, myself, and I have the scars to prove it!

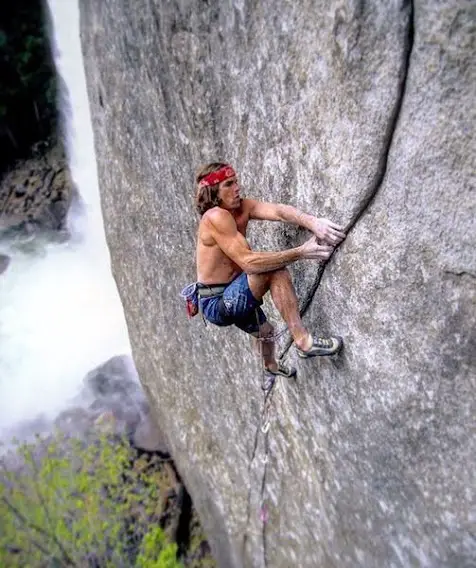

Ron Kauk

Ron Kauk is an American free climber who is known for pushing the envelope on hard climbs. He and others of the core Yosemite climber’s circle did the first free-ascents of ultra-classics like Astroman on Washington column – 5.11c and Separate Reality in the Lower Merced River Canyon – 5.12a. He also put up Crossroads – 5.13d/14a and Magic Line – 5.14a/b. To date, the only other person to lead Magic Line has been his son, Lonnie.

Oh yeah, and he was the first to climb Midnight Lightning, the most famous boulder problem in the world! The story is that John Bachar sat by for the first ascent with a flake of chalk, idly drawing a lightning bolt on the boulder as Ron made history. To this day, climbers have donated a crumb from their bags here and there, preserving the image like cavemen writing down their histories.

Lynn Hill

One of my biggest heroes in the climbing world is Lynn Hill. Lynn was young when the era of the Stonemasters came along, but that came with its own advantages. With the invention of the Spring Loaded Camming Device, what we know today as a “Cam,” in ’78, and some cross-over in climbing culture between the U.S. and Europe – namely, bolting for upward progress – huge leaps were being made in the sport. Lynn Hill was at the forefront of these advances.

In 1986, Hill traveled to Europe and was introduced to the art of sport climbing. In the late eighties, she jumped aboard the competition circuit, and won! At the peak of her career, she was one of the greatest sport climbers on the planet. She was the first woman to climb 5.14 and one of the first people to turn climbing into an actual job, making enough money from competitions and sponsorships to sustain a climbing lifestyle.

In the early nineties, she quit the competition series and returned to where she had gotten her start: Yosemite. In 1993, Lynn Hill became the first person – man or woman – to free-climb The Nose of El Capitan. She put the crux pitch at 5.13b, which was later upgraded to 5.14b. One year later, she came back and completed the same feat, but in the span of 24 hours!

John Bachar

One of the most daring free soloists to ever live, John Bachar’s ascents sent shockwaves through the climbing community. He was one of the first to train for strength and endurance, spending all of his free time lifting weights at his campsite. He also established the mega runout testpiece for Tuolumne slab/face called Bachar-Yerian – 5.11cX which, frankly, makes me shiver just to think about.

He was quite similar to Royal Robbins in a way. He believed in climbing as pure as possible from the ground up and leaving no trace behind. That’s why his main method of climbing was by free soloing. The Stonemaster era was when climbers went from being smelly dirtbags to celebrities and athletes with sponsorships. Bachar was not a fan of that, and a few heated feuds forced the Stonemasters to part ways.

While the rest of the Stonemasters went off to competitions, magazine photoshoots and movie sets, Bachar stayed true to his climbing ethics, free soloing till the day he died.

While all good things come to an end eventually, one thing’s for sure, Bachar put the word master into stone.

The Stone Monkeys & Beyond

Dean Potter

With all of the vision of Jim Bridwell and all the strength of John Bachar, Dean Potter blazed a serious trail on what was considered possible in Yosemite. There are many elite-level routes that Dean has soloed, often barely within range of his absolute limits. He helped to popularize BASE jumping in the park and even invented his own sport, which combined his two passions: free soloing and BASE jumping, an invention called “Free Basing,” which permitted him to solo even closer to the extremes of his climbing abilities.

Dean Potter and Sean Leary held the speed climbing record on The Nose for many years, something they traded blows with Hans Florine for. In 2010, the duo completed the climb in 2:36:44. It was almost a decade before their record was surpassed by Brad Gobright and Jim Reynolds, two of the Yosemite SAR crew, who ascended the main buttress in 2:19:44, a time which was subsequently thrashed by Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell, who climbed the El Cap massif in a staggering 1:58:07.

Tommy Caldwell

I’ll only say this once: Tommy Caldwell is the greatest big wall climber of all time. I dare you to argue with me.

Caldwell has secured his place in the history books as the man who has dreamed and established more routes on El Capitan than any other person. To climb even ONE of these routes free is something that only a handful of elite climbers have ever done; Caldwell has six to his name. And since he’s too humble to spray about it, I guess I have to do it for him.

- FFA of the West Buttress of El Capitan – 5.13b

- FFA Dihedral Wall of El Capitan w/Beth Rodden – 5.14a

- FFA Magic Mushroom on El Capitan w/Justin Sjong – 5.14a

- FFA Dawn Wall on El Capitan w/Kevin Jorgeson – 5.14d

- FFA Lurking Fear on El Capitan w/Beth Rodden – 5.13c

- FFA The Shaft on El Capitan w/Nick Sagar – 5.13c

The amount of mastery and commitment required to do what Tommy Caldwell has done is beyond imagining. Oh, and did I mention that he only has nine fingers?

Beth Rodden

For years, Tommy Caldwell and Beth Rodden were the power couple of the climbing world. They completed innumerable first ascents together and separately, mostly on El Capitan, but they also traveled the world, developing and checking off one hard climb after another. However, Beth’s track record speaks for itself, and she does not need to stand next to Tommy Caldwell to shine.

One of Rodden’s most notable accomplishments is Meltdown, a supposed 5.14c crack in Yosemite Valley. What is most amazing about this first ascent is that it has yet to be repeated. 5.14c is Rodden’s best guess at the grade! It could well be harder than 14c. Plus, it’s right next to the road, not a thousand feet up the face of El Cap, so you can bet that the self-styled “hard boys” have all tried.

Alex Honnold

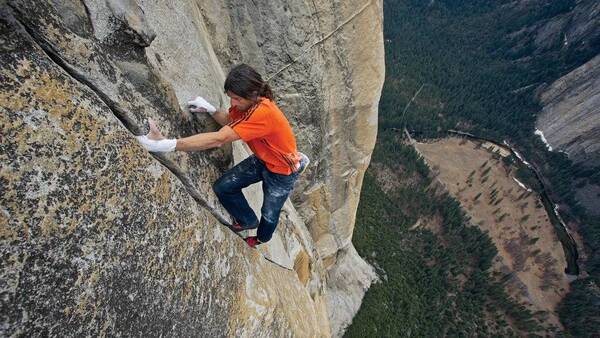

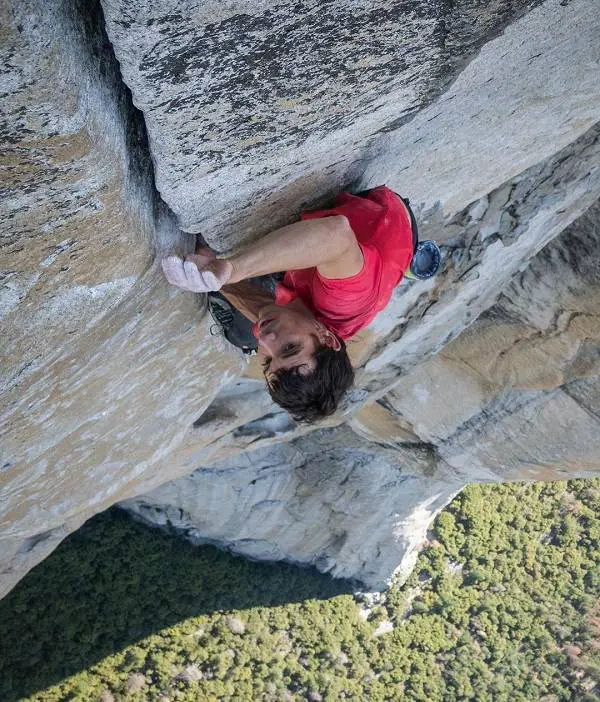

Sigh… Fine. He’s all we ever hear about anymore, but credit where credit’s due, I guess. Alex Honnold is the greatest free-soloist that has ever or probably will ever live. His blistering speed records and solo linkups notwithstanding, in 2008 Alex Honnold free-soloed the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome in just over two hours.

He would dance his way up many other difficult and hackle-raising routes, but perhaps none more so than Freerider on El Capitan – 5.13a, a feat which represents one of (if not THE greatest) athletic accomplishment in history. This daring stunt, and the Oscar-winning documentary that went along with it, have made him the most famous climber in the world right now and the best free solo climber of our time.